Educators crying in their cars, trying to convince themselves they can get through another day. Bite marks, bruises, and the daily fear of violence from the elementary students they teach.

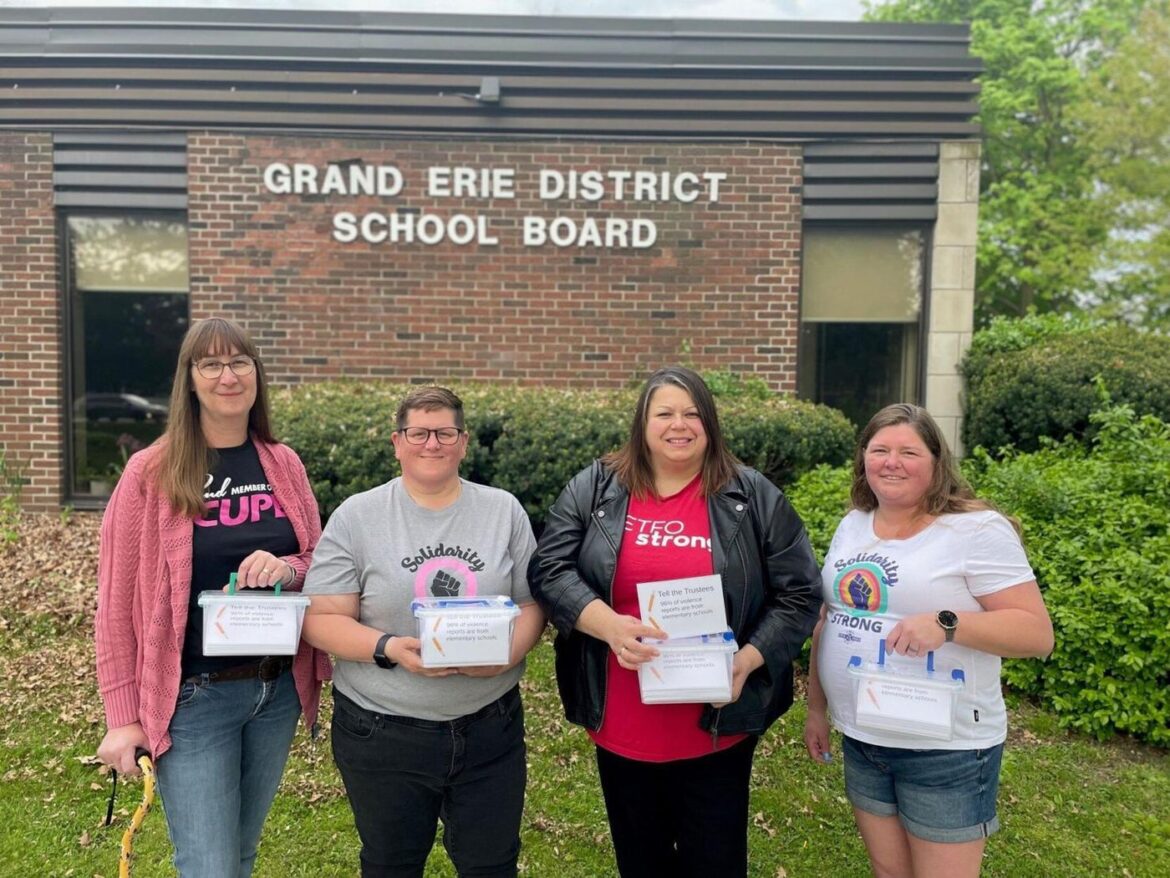

These were a few of the challenges handwritten on postcards delivered to the Grand Erie District School Board (GEDSB) by the presidents of four unions representing Brant-area education staff.

The representatives hoped the words would inspire the board to allocate some of its $11.1 million budget surplus to support staff.

None of the stories came as a surprise to the union heads from CUPE 5100, ETFO Occasional Teacher Local, ETFO DECE Local and ETFO Teacher Local, who represent more than 2,800 education workers in GEDSB elementary schools.

Still, reading through the challenges of local education workers was “devastating,” said Amanda Baxter, president of the Grand Erie District School Board Occasional Teacher Local.

Especially because they believe additional supports are key to addressing student dysregulation that is manifesting in increased school violence, Carolyn Proulx-Wootton, president of the Grand Erie Elementary Teachers’ Federation, told The Spectator.

But while Proulx-Wootton said GEDSB acknowledged receiving the postcards in May, the approved budget didn’t align with the surveys that pointed to a need for a substantial increase in educational assistants (EAs) and other direct student supports in classrooms, she said.

For instance, the board budgeted for an increase of 15 EAs in 2024-25.

In reality, closer to 40 additional EAs are needed to match the needs of the projected increased enrolment of 900 additional students next year, Sarah Kuva, president of CUPE 5100, told The Spectator.

“Our feelings are that there is just not enough allocation of educational systems for what we have and what we are seeing in our schools now to provide the correct level of support,” Kuva said.

Dysregulated youngsters

So what are elementary educators seeing?

“Starting in kindergarten, students are so dysregulated and as they continue to grow, the violence continues,” Baxter told The Spectator.

The cause is multifaceted.

Large kindergarten classes with lots of individual needs, pandemic aftermath, and youngsters who still haven’t learned how to manage their “big feelings” are all factors, Steph Scott, an ECE and president for the Grand Erie DECE Local, told The Spectator.

Proulx-Wootton said they’re also seeing “more and more students on the spectrum” who haven’t been able to get the tools they need outside of school due to “disastrous cuts by the Ford government.”

What this means for their peers can vary.

Dysregulation interrupts learning, particularly if the teacher needs to attend to the student, Proulx-Wootton said.

In more severe situations, students have to evacuate their classroom — sometimes multiple times in a day — as a result of unregulated students, Scott said.

Support staff are key in helping to identify students who may have additional needs, and helping to de-escalate dysregulated students so teachers can continue teaching, the union presidents said.

The ask

In a joint media release following a presentation of the draft budget, the four union heads flagged an urgent need for more EAs, psychologists, behavioural consultants, counsellors, child and youth workers, communicative disorder assistants, and speech language pathologists.

The release also said a minimum of one full-time special education learning resource teacher is necessary in each school to “meet the promise of an inclusive education system.”

A chart in the GEDSB 2023-24 special education plan document shows the following full-time equivalent specialized services staff for the board:

• Seven speech-language pathologists.

• Seven communicative disorder assistants.

• Three board-certified behaviour analysts.

• Nine and a half social workers.

• Six psychoeducational consultants.

• 25.5 child and youth workers (with one additional Indigenous child and youth worker).

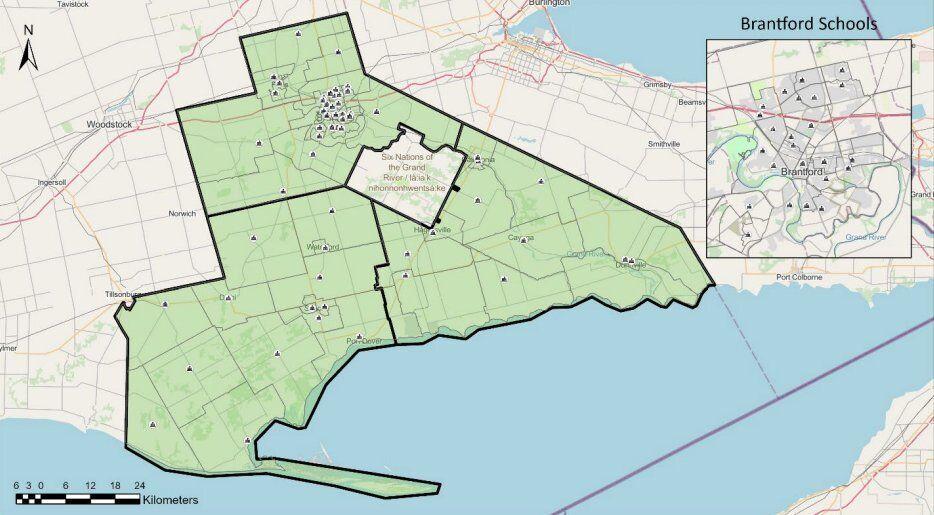

These staff are tasked with overseeing more than 26,000 students, spread across a geography of around 4,000 square kilometres.

Additionally, there are approximately 340 EAs in GEDSB, working out to about one EA for every 76 students in the board.

About 183 of the EAs are in Brant-Brantford schools.

The EAs are assigned to students with medical, behavioural and other needs, said Kuva.

Students with higher medical needs are partnered with an EA who works one-on-one with them throughout each day, including recess and sometimes for transportation to and from school, Kuva said.

For learners with other needs, an EA is often responsible for multiple students, according to Kuva.

The school board told The Spectator stakeholders are invited to provide input into the budget development each year through a survey to “gauge priorities, concerns and requests for additional investment.”

The feedback from that process “is reflected in the decision to add 15 permanent educational assistant positions,” after “carefully weighing the many important and often competing requests for the limited funds available,” the statement said.

An $11 million surplus

The board anticipates a student enrolment of 27,900 next year, approximately 900 more pupils than the 2023-24 school year.

At a June 24 board meeting, the school board approved a balanced budget at nearly $421 million, with slightly more than $397 million allotted to operating costs and $23.5 million for capital costs.

In statement to The Spectator, the school board said its approach to allocating resources is “balanced and sustainable while still aiming to have an ambitious impact on educational opportunities and supportive services.”

With increased pupil enrolment driving revenue, the statement said “most of the increase in staffing is dedicated to classroom positions that directly support the needs of learners, including 49 new teaching positions and 15 permanent educational assistant positions.”

Additional investments highlighted in a press release included:

• Transportation funding.

• Professional development.

• Technology infrastructure.

• And “a significant portion of funding” dedicated to the Grand Erie math achievement action plan.

However, the unions argue not enough investment is “being made into humans,” Proulx-Wootton told The Spectator.

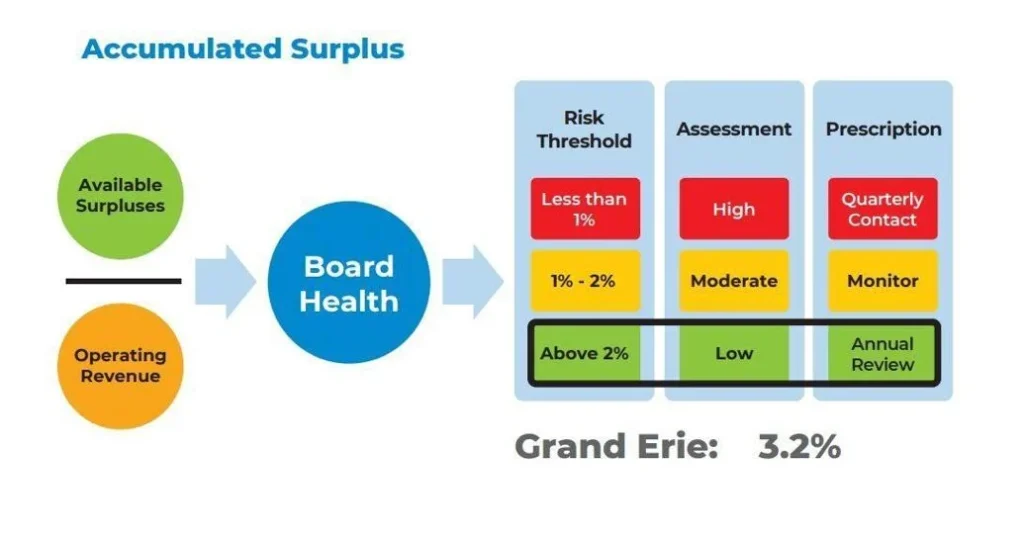

“We know that the board received less money, but we also know they’re sitting on an $11.1 million surplus from this year,” she said, calling it “painful” that the school board didn’t use some of that surplus to hire additional student supports.

To add the additional 25 EAs the union representatives say are needed, it would cost the board around $1.6 million, according to the unions.

Some boards, like the Greater Essex District School Board, have elected to submit budgets with a deficit this year, because it “could not and would not have the programs and the services they needed for their students” otherwise, Proulx-Wootton said.

In response to questions about the surplus, GEDSB said in a statement that the reserves are “the result of operating surpluses from previous years and reflect the Ministry of Education’s encouragement to maintain two per cent of its operating allocation.”

The statement went on to say “Grand Erie’s practice is to maintain a healthy reserve balance. One of the pillars of maintaining this is the development of a balanced budget without relying on these reserves.”

The board said it “looks forward to continuing to work with our unions and federations to ensure student needs are met and in line with our strategic priorities.”

Looking ahead to the new school year, Proulx-Wootton shared appreciation of the union members for continually meeting students’ educational needs “wherever they’re at.”

She said the unions continue to believe in “an inclusive education system with all of our students with their age-related peers progressing through elementary school.”

But without the necessary supports, Proulx-Wootton said “it feels like abandonment.”

By Celeste Percy-Beauregard, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter