597

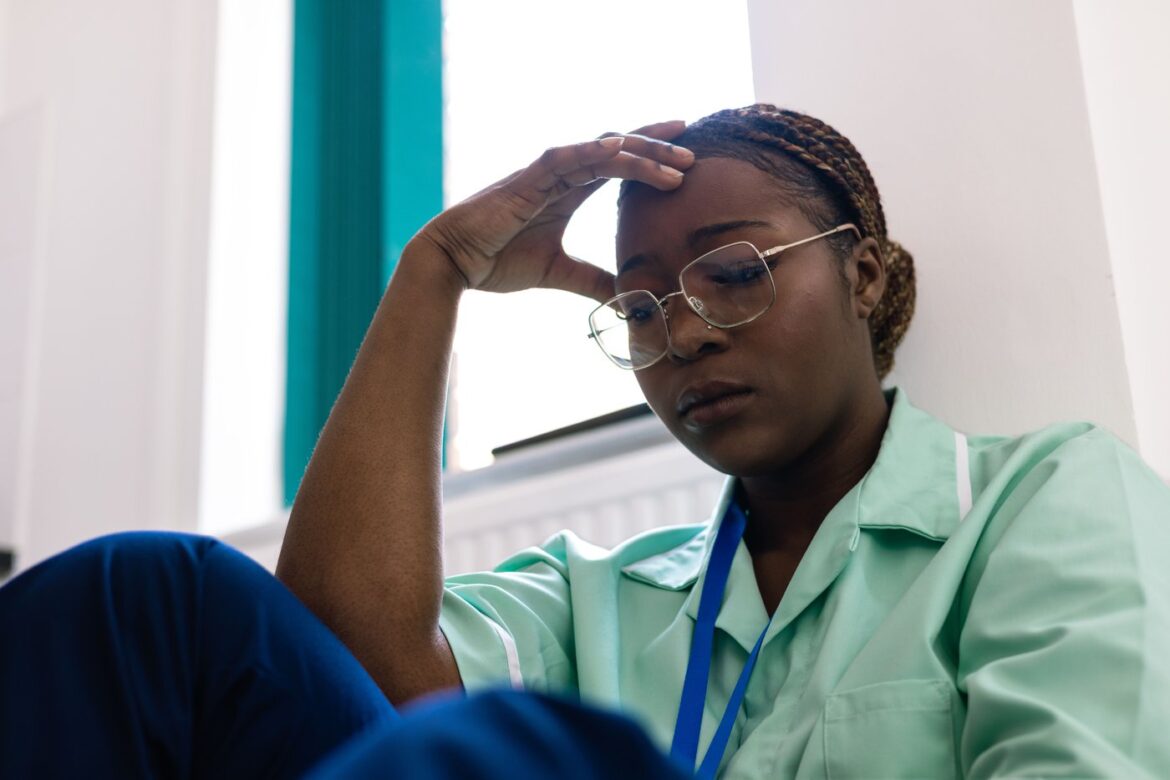

Understanding moral injury in frontline workers is the focus of two days of events at MSVU this Feb 13 and 14. SolStock/Local Journalism Initiative