300

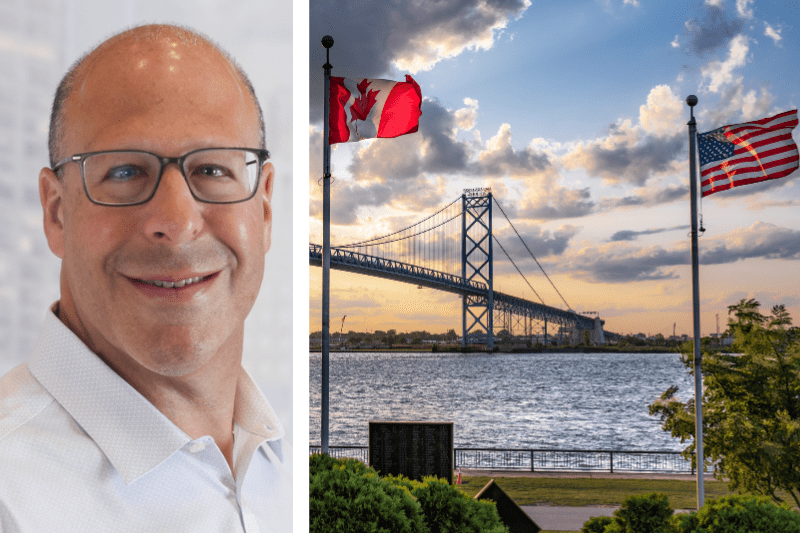

Stuart Rudner says tariffs and a trade war don't change any of the regular workplace rules around layoffs and terminations. On the right is a view of the Ambassador Bridge connecting Windsor, Ont., and Detroit.