Ask anyone whether they consider themselves fair, tolerant, open-minded, and inclusive, and the vast majority will say yes. We always think we’re doing the right thing and that our decisions are objective, guided by logic instead of emotion.

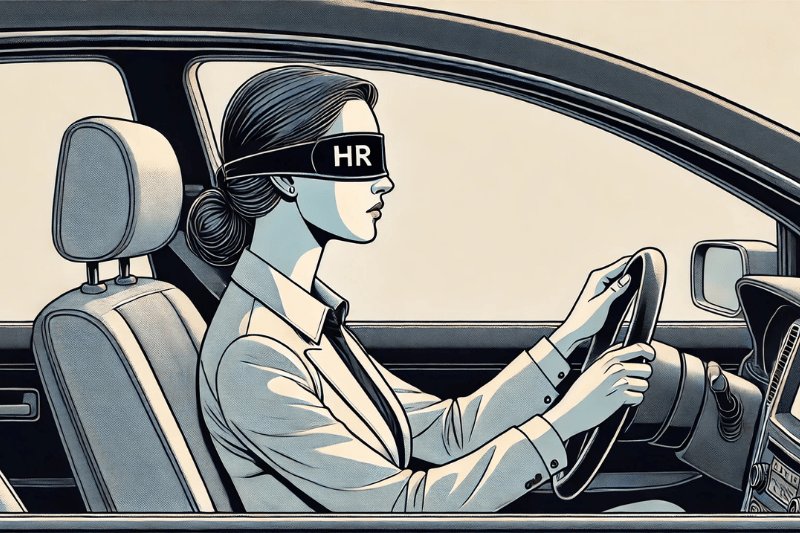

However, biases and filters are at work in our brain that we are not aware of, which can lead to mistakes when we gather, assess, and weigh data. Being oblivious to bias is what makes recruitment and selection such a challenge.

When we review resumes and interview candidates, we are unaware of much of the processing that goes on in our brain, which is often lightning-fast. Evolution has equipped us with the ability to make friend-or-foe assessments within seconds of seeing someone, which was a crucial survival skill a million years ago. The proof? Those who guessed wrong are no longer here.

This prehistoric quick scan is still with us in modern times. It’s triggered when we are on a solo run and a stranger appears, and when we pick up job candidates from the reception area. First impressions are instinctive and it’s almost impossible to reconstruct what happens in those five seconds. And if a candidate is “out” after the first interview and you ask your fellow interviewers why, it’s usually a matter of “I can’t quite put my finger on it,” or “I just didn’t like him.” It’s often a struggle to come up with a rational explanation – that part is filled in later when we update executives. We are great at rationalizing decisions after the fact, framing our prejudice with a narrative.

Science suggests that if someone makes a positive first impression, we tend to fit whatever comes next into that positive frame. When the candidate botches the answer to a question, we force-fit the “bad” answer into the “good” template, and justify this by thinking, “They must have meant this or that,” or “Probably just nerves.”

First impressions and familiarity

If a candidate leaves a lousy first impression, we send information that confirms this directly to our hard drive, while ignoring information that doesn’t align. No matter how brilliant the candidate’s subsequent answers are, it’s almost impossible to overcome the interviewer’s initial bias. In other words, our brain absorbs information that confirms its first impression and ignores information that doesn’t fit. It’s our mind in action at processing inputs.

When it comes to hiring, the bias we’re most familiar with is “like.” When interviewers like certain candidates, these rise to the top of the list. At the root of this lies an unconscious bias: the “like me” factor. If the candidate went to the same university as the interviewer, grew up in the same small town, or has a hair style similar to that of the interviewer’s beloved spouse, the interviewer will embrace what is familiar. This is disastrous for organizations as it breeds sameness, the culture goes stale, and the lack of dissenting opinions prevents debate.

As humans, we tend to find comfort in familiarity, structure, and routine. We’re biased in favour of the status quo and going with the flow, and against change and trying new ways. Routine is easy, change is hard. This is why kids watch the same Disney movies over and over: knowing what’s coming reassures them.

Another form of bias is the perceived value of physical perfection. In North American culture, good looks are associated with a range of commendable traits, such as integrity, honesty, and intelligence. Plus, according to Hollywood, if you have great skin, you’re always happy and you end up on a yacht crushing margs all day with other models. As Peter Collier and David Horowitz said in The Kennedys: An American Drama: “We’re always tempted to impute unlikely virtues to the cute.”

This explains why we see everybody and their uncle working out in gyms to get washboard abs, trying one diet after another, running long-distance, attending yoga classes, and experimenting with Botox, and commercials suggesting that an angular face and great hair equate to mental acuity and being perfect for a fast-paced environment. (Before I die, I want to see the phrase “slow-paced environment” in a job ad.)

Despite all the talk about strong values and high standards, hiring decisions are often influenced by the fact that someone on the inside knows one of the candidates, which makes that person a safer bet. In Pedigree, Lauren Rivera of Northwestern University in Illinois suggests that hiring conversations can be more about reaching consensus than vetting people accurately. And on the topic of diversity versus more-of-the-same, Christine Riordan wrote In Harvard Business Review that “many organizations unknowingly have ‘prototypes for success’ that perpetuate a similarity bias and limit the pool of potential candidates.”

Organizations express a commitment to diversity and inclusivity, but it’s often curated reality. If they are hesitant to bring in people with a fresh perspective IRL, diversity and inclusivity will be collateral damage. True diversity isn’t a matter of quota, labels, and targets, but of personality, thinking, talent, outlook, and opinion. It’s about who the candidate is and what they bring to the table. In this vein, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. referred to “the content of their character.”

At the tail end of the hiring process, bias comes back into play when we check references. The first problem is lack of verifiability and the second that, by definition, references are biased because they have worked with the candidate. In most cases, references provide positive information, ranging from good to glowing. Which makes sense, as candidates typically give references whom they expect to say good things about them. Right? Well, not automatically.

Over the years, I’ve talked to hundreds of references. I go into these calls with a bias, as I’m looking for confirmation of information that my filter interpreted as positive. I want reassurance that my impression was correct. However, on several occasions, the references’ feedback required a course correction, which was an unsettling experience. It forced me to recalibrate. I had an example where a reference, when asked to rate the candidate’s performance on a scale of 1 to 10, paused for three seconds and then replied, “I’d say a 7” (which my brain instantly computed as a 5).

Other references provided outright puzzling information. One said that the candidate tried out new ideas and, when I asked for an example, replied “None come to mind.” (Lol wut?) Another contradicted himself by saying that the candidate would ask for help if he was unsure and then, three questions later, under “areas for improvement,” stated that the candidate “has to learn how to ask for help.” These were rattling experiences, as the new information didn’t fit my bias (insert record scratch sound).

HR’s role in combatting bias and encouraging diversity

We shouldn’t harbour illusions about changing millions of years of human evolution, but HR has a definite role in applying proper procedure and pushing back when bias enters the conversation. Our role as HR practitioners includes being wary of fit and other delightfully vague criteria in an atmosphere of balloons and crayons.

During the hiring process, we need to keep in mind that we are looking for the knowledge, skills, and expertise listed in the job posting and for the passion the organization needs to move ahead, rather than picking complacent duds, like a comfortable old shoe. As a friend said recently, “You cannot become more efficient if you have the wrong people.”

From its unique position, HR can make a difference by probing for submerged biases, dropping “pings” like navy destroyers using sonar to detect submarines and force these to the surface.

An earlier version of this article was originally published in Municipal World