When 10,000 Air Canada flight attendants defied a federal back-to-work order last month, they carried the same spirit of defiance that sparked Labour Day more than 150 years ago.

Their three-day strike over unpaid ground work and other grievances echoed the Toronto printers who walked off the job on March 25, 1872, demanding workplace fairness. Both showed that lasting change often requires challenging authority.

The parallels go beyond protest. The 1872 strike helped legalize unions and created Labour Day. Today, new disruptions come amid major shifts in Canadian labour relations, including the June 2025 federal anti-scab law and youth unemployment hitting 14.6% in July.

The first labour revolution

In 1872, printers demanded a reduction from 12- to 9-hour workdays without a pay cut. Union leader John Armstrong rallied workers facing 10–12 hour shifts, six-day weeks, and no legal protections.

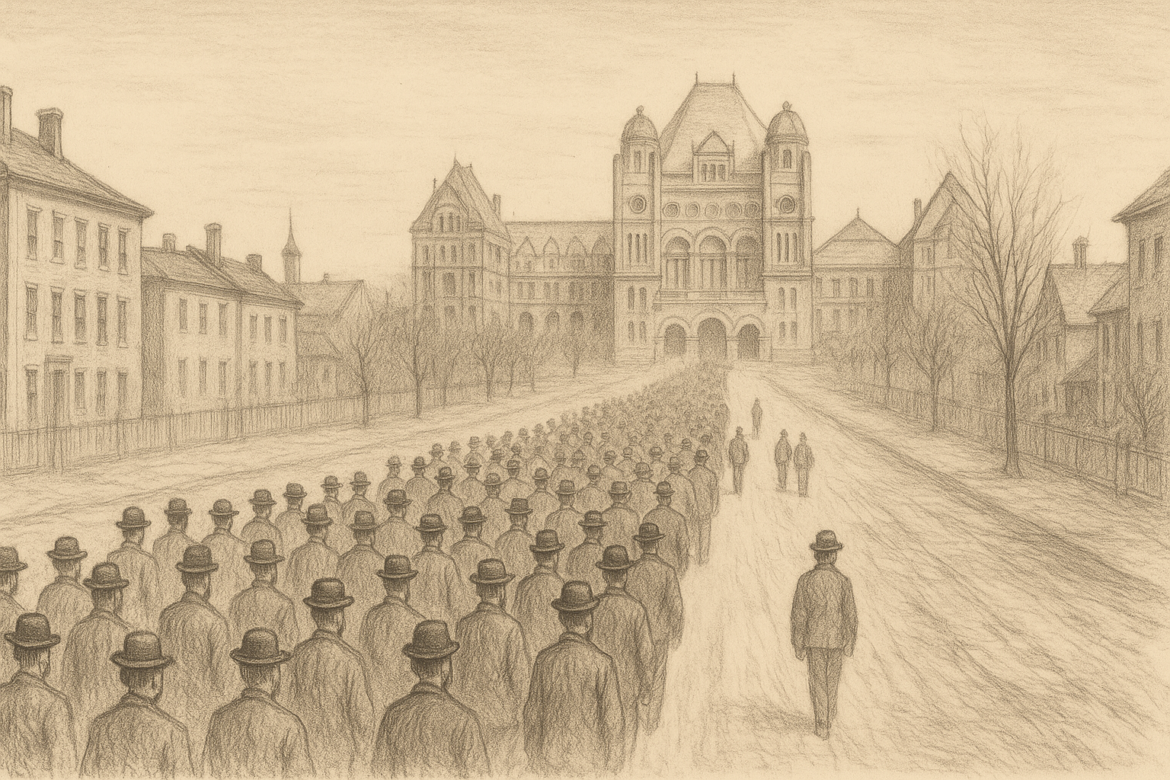

When employers dismissed the demands as “foolish,” workers struck. On April 15, 1872, the Toronto Trades Assembly led a demonstration of 10,000 people — one-tenth of the city’s population — from King Street to Queen’s Park. That’s the equivalent of 700,000 Torontonians descending on the legislature today.

The next day, 24 strike leaders were arrested for criminal conspiracy. Union activity was illegal under British law.

The arrests backfired. Three days later, Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald introduced the Trade Union Act, which legalized unions. It passed on June 14, 1872, laying the foundation for modern labour relations.

Turmoil in the present

Today’s tensions follow similar patterns. The Air Canada strike challenged federal intervention much like the printers defied the ban on organizing.

CUPE president Mark Hancock’s comment — “If it means folks like me going to jail, then so be it” — recalls Armstrong’s willingness to face arrest.

The federal anti-scab law (Bill C-58) is another turning point, reshaping federally regulated sectors from banking to railways. Labour Minister Seamus O’Regan Jr. called it a “seminal moment in Canadian labour history.”

Meanwhile, youth face recession-level unemployment. Statistics Canada reported July jobless rates of 26.4% for Arab youth, 23.4% for Black youth, and 20.5% for Chinese youth. These struggles mirror the hardships of immigrant workers who backed the Nine-Hour Movement.

Progress and persistent challenges

Labour Day’s meaning has grown from shorter workdays to broader protections, training, and economic security.

Employers now face new “nine-hour” demands. While 32% of job seekers want more flexibility, 95% of HR managers say finding skilled talent is difficult.

The gig economy employs 28% of Canadian adults, with most holding multiple jobs and many lacking benefits. These conditions resemble the insecurity of 1872.

Statistics Canada reported employment fell by 41,000 in July 2025, while long-term unemployment climbed to its highest level since 1998.

A living legacy

Labour Day is less about nostalgia than about recognizing that work relations are never settled. The holiday is a reminder that progress often begins with disruption.

The printers’ nine-hour demand seemed impossible until it became standard. Today’s calls for four-day workweeks or gig worker benefits may sound equally unrealistic — until one day they don’t.