By Kate Burridge and Howard Manns

These days, human resources (HR) departments want us to use official titles for jobs. But we know the social truths of a job — how well that job gets done, whether we like the person doing it — are much more complex.

Nicknames for jobs help us manage workplace performances, personalities and power beyond HR spreadsheets — and they can be a lot of fun.

Cooks, bastards and babblers

Australians like to call things as they are — and it’s always been that way, as this famed army example illustrates:

Officer addressing a group of men: “Who called the cook a bastard?”

One man shouting above the others: “Who called the bastard a cook?”

Sometimes we’re very direct, but other times there’s a hidden, and often cheeky, hierarchy at work. During the first world war, one ANZAC magazine warned that army cooks ranged from the “grease-besmudged babbler” to the “natty, smart-looking chef”. Babbler is rhyming slang from “babbling brook” for “cook”. Babblers were presumably better at their job than “baitlayers”, “slushies” or “poisoners” — other terms for cooks in the bush.

How not to boil the wrong Billy

But workplace nicknames are more than just pointing out someone who “wouldn’t work in an iron lung” or is more likely to “pick up a brown snake than a rake”. Nicknames are also about creating a friendlier workplace.

Humour and informality are key ingredients for workplace nicknames — Aussies have a knack for keeping things light-hearted. Think of the way “sickie” has flipped its meaning from a day’s sick leave to a day’s leave without being sick.

In the bushie era, some joked that any two men were apt to be named Bill or Jim. The swaggies needed ways to tell all their Bills apart, so you might end up with “Old Billy”, “Young Billy”, “Tall Billy”, “Thin Billy”, “Fat Billy” or “Billy the Rooster”. And, of course, true to Australian character, “Tall Billy” might be short, “Thin Billy” might be fat, and a red-headed Billy was almost certainly called “Bluey”.

One understated but important way to make a “Bill” or “Jim” more likeable is to make them a “Billy” or “Jimmy” — in other words, to add an “-ie” or “-y”, or an “-o” (as in a name like “Johno”). These sorts of endings abound in English, but Australians go a step further than British and Americans in terms of frequency and creativity.

Moreover, the Australian “-o” ending can trace its origins to occupational nicknaming. The earliest Australian examples (“milk-o”, “rabbit-o”, “bottle-o”) date from the late 19th century. All are clipped names for people’s jobs (milkman, rabbit-seller, bottle-collector), though sometimes written with “-oh” because they echo the street vendor calls.

These endings are called diminutives — or hypocoristics, if you want the fancy term. Basically, they’re pet-name endings we tack onto words (often shortened) to show warmth or friendliness. And sure, names like “Johno” and “Susie” can sound affectionate, but most Aussie diminutives like “journo” or “sparky” aren’t about being cute.

It’s still a puzzle which words get which ending. We happily talk about “sparkies”, “chippies” and “brickies”, but never “sparkos”, “chippos” or “brickos. “Ambos”, “garbos and “musos” roll off the tongue, but “ambies”, “garbies” and “musies” don’t. And why are there gaps? People who build are “builders”, not “buildos” or “buildies”.

Much remains unknown about these endings. But what we do know from research that Evan Kidd and colleagues have carried out is that these playful endings really do have social power — the little “-ie”/“-y” and “-o” tags help hold Australian English speakers together.

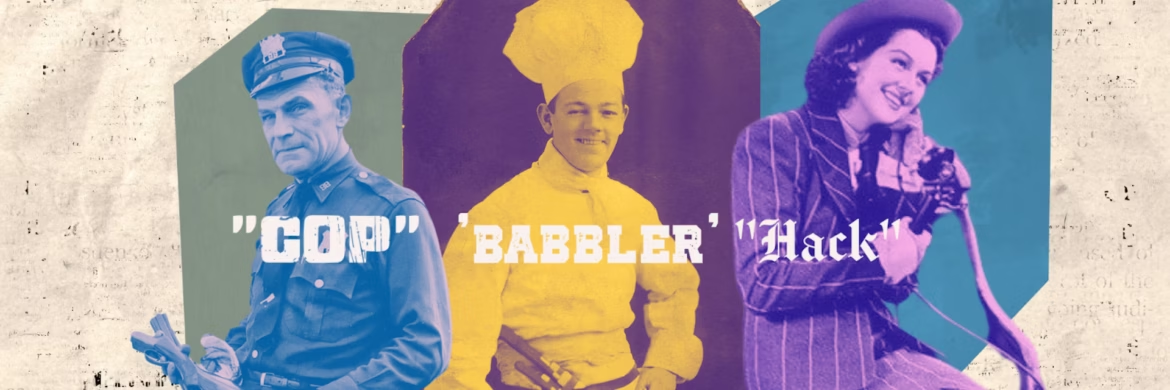

Shrinks, cops, hacks and quacks

Nicknames also help us cope with the power certain occupations wield over us, and the degree to which we trust those occupations.

For instance, the exact origins of “shrink” for psychiatrist are speculative, but all point to some anxiety about the people who help us with our anxieties. The term first emerged as “headshrinker” and almost certainly owes its origins to the literal practice of head shrinking (as performed by the Jivaroan Indigenous people of South America). The rather grisly label for psychiatrist made its print debut in Hollywood slang in the 1950s — and an on-screen appearance in Rebel Without a Cause certainly popularised the term.

Perhaps the process was originally seen as taking air out of the inflated egos so rife in showbiz — or letting air out of people’s worry-swollen thoughts. Others suggest the term echoes lobotomies once used on those seen as dangerously violent. Or perhaps it’s simply that shrink reflected the nervous suspicion at the time about what psychiatrists really did to people’s heads — and black humour took the edge off.

More than a few people have also shown a distrust of police officers — who garner nicknames like “five-o” (from the famed television show Hawaii Five-O) or “pigs” and “grunters” (both have entries in James Hardy Vaux’s 1812 dictionary of convict slang).

Of all the nicknames, “cop” is perhaps the best recognised. Certainly, it’s sparked the most interesting narratives about how it came to be. One suggestion is that it was originally back slang from “police” (like “yob” from “boy”) — but there’s too much consonant dropping required here for this to be the most likely story!

Others link it to copper buttons, badges or batons. There are also a number of backronym explanations (retrofitted acronyms, where the words are chosen after the fact to match the letters). It’s often claimed, for example, that “cop” stands for “constable on patrol”. In fact, a copper was simply one who cops (that is, catches criminals).

Journalists also draw scrutiny and have been called “hacks”. In the 1500s, “hack” (short for “hackney”) referred to a horse for hire, usually an inferior or worn-out one. In the 1600s, “hacks” extended to people — “hacks” were drudges or lackeys. Later it specialised to refer to those hiring themselves out to do literary work, usually of poor quality. By the early 1800s, “hack” increasingly was used for journalists (originally “newspaper hack”). And, like so many derogatory names, it’s now more usually affectionate or ironic.

The curious word “quack” has emerged as a catch-all term for those promoting quick and easy cures or get-rich-quick schemes. “Quack” was a shortened form of “quacksalver”, in use since the 1600s for the medical charlatan (although as historian Roy Porter has emphasised, some quacks were decent, caring, well-intentioned people, offering cures when mainstream medicine failed). The inspiration here was the quacksalvers’ loud and bragging promotion of their products.

Our workplace “bean-counters” (US slang since the 1970s) turn people into KPIs, but workers are bound to stay focused on whom we love, whom we fear and whether a bastard’s a cook or a cook’s a bastard. From quacks to babblers, our workplace language isn’t determined in spreadsheets — it’s determined at “smoko”.

Kate Burridge, Professor of Linguistics, Monash University and Howard Manns, Senior Lecturer in Linguistics, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.