By Amr Saber Algarhi, Sheffield Hallam University and Konstantinos Lagos, Sheffield Hallam University

Inflation in the UK has fallen to 2.3% in the year to April – the lowest figure for almost three years. Before this, prices at UK tills were relatively low and stable for many years. But in 2021 they started rising, causing a continual increase in the price of goods and services – otherwise known as inflation.

At first, policymakers believed this higher inflation would be transitory, with the main issues being confined to a few industries, such as used cars and computer chips. Supply chain issues with computer chips slowed the manufacture of new cars, which in turn put pressure on the used car market and forced up prices.

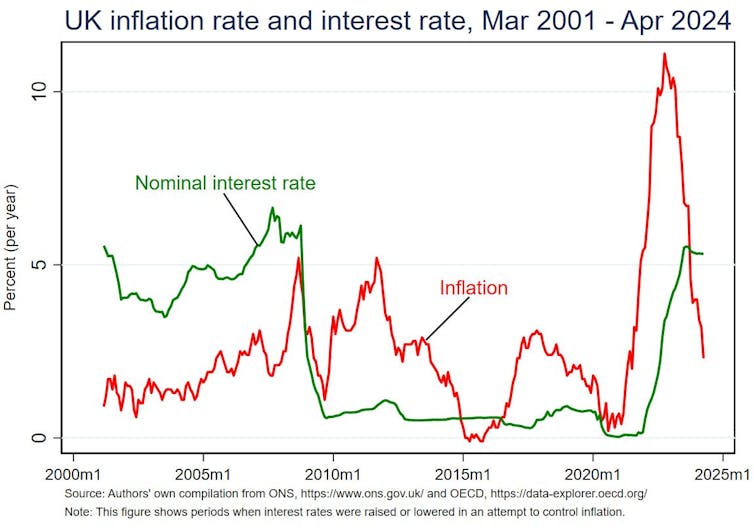

That’s why the Bank of England was initially reluctant to raise interest rates. This would be the usual monetary policy response, as a means to curb spending. However, prices continued to rise in 2022, as the Russia-Ukraine war hit supply chains and energy costs.

The result was inflation levels reaching 11.1% in October 2022 – the highest in 41 years. That put a huge squeeze on UK household finances, since high inflation erodes the purchasing power of wages and income.

While the April figure is still above the government’s 2% target, it has renewed hope that the UK may soon return to a relatively stable inflation environment.

So could this cooling inflation finally bring fatter pay packets for UK workers? Well, when inflation is positive, the purchasing power of our money gradually falls. For example, the average price of an 800g loaf of bread in November 2021 was £1.06, compared to £1.36 in November 2022. This means that in 2022, you needed 28% more cash to buy the same loaf.

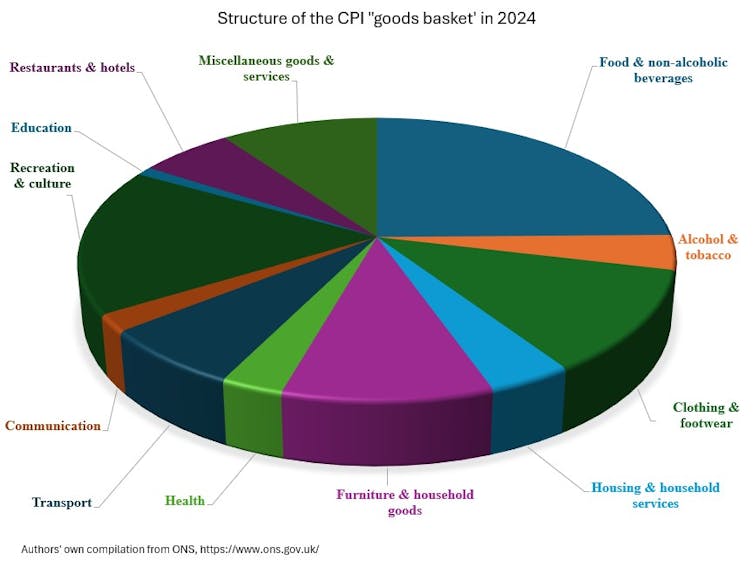

Inflation is calculated by examining an index that tracks the prices of various everyday items (the “goods basket”), with the Consumer Price Index (CPI) being the most frequently used metric. CPI incorporates a range of goods, which account for the spending habits of both UK residents and foreign visitors and can measure price changes. The contents of the basket are reviewed annually to reflect changing spending habits – alcohol hand gel was added in 2021 during the COVID pandemic and then removed again this year, for example.

Declining inflation rates don’t mean prices are actually falling. It simply means that they are still increasing, just not as swiftly. But what does inflation do to our wages? To assess this, we need to understand the difference between real and nominal wages in terms of purchasing power.

The nominal wage is simply the pay you receive, say £1,000 each month. However, with annual inflation rising by 2.3%, the actual purchasing power of that £1,000 now would be less than it was one year ago. This true measure of how much your money can buy is called the “real wage”, and in this example it would be £978 (2.3% lower than the £1,000). This is important, as it is real values over time that truly show how standards of living have changed.

Inflation’s grip on wallets

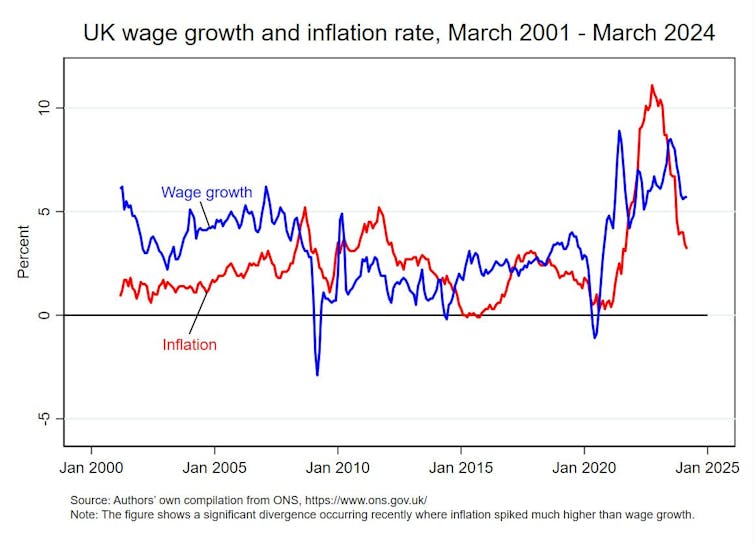

One way to counter the loss of real wages due to inflation would be to increase nominal wages. In fact, nominal wage growth has been on the rise in the UK since 2020. However, while wage growth can compensate for inflation increases in a healthy economy, this has not been the case for UK workers over a long period of time. Soaring prices for essentials including food, energy and housing have swiftly exceeded wage gains, undoing the effect of nominal wage rises.

And this has been happening in an extraordinarily tight UK labour market. After the COVID disruption, employers had to pay higher rates to recruit and retain staff. This produced a vicious cycle, with workforce shortages not only producing a surge in wage growth, but also creating even higher inflationary pressures. This was because businesses increased prices to compensate for rising labour expenses.

Higher inflation combined with reduced consumer purchasing power may lead to less demand for goods and services, which can cut the profitability of businesses. With lower profits, businesses become much less motivated to increase wages. This negative spiral can make it more difficult to escape stagnating wages and persistent price increases.

Nevertheless, in the first quarter of 2024, average total earnings grew by a robust 5.7% compared to a year earlier. This signified a 2.1% gain in real terms when adjusting for inflation. And it indicated that falling inflation alongside larger wage increases can indeed boost UK pay packets, by increasing households’ real purchasing power.

If inflation continues to cool, workers will have an opportunity to break free of the cycle of real wages lagging behind living costs. This should help them regain some of the ground lost during the years when inflation outpaced wage growth. This is crucial not only for improving standards of living, but also for stimulating economic growth.

On the other hand, businesses should also find themselves in a better financial position to provide competitive pay raises. Arguably, private companies may have more flexibility to adjust compared to public ones.

Ultimately though, the pace at which businesses can adjust pay scales and budgets will depend on their overall financial health, their staffing needs and whether the broader economic outlook continues to improve. And of course a lot will ride on inflation, and whether prices continue to stabilise over the long term.

Amr Saber Algarhi, Senior Lecturer in Economics, Sheffield Hallam University and Konstantinos Lagos, Senior Lecturer in Business and Economics, Sheffield Hallam University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.