By Alexandre Hudon

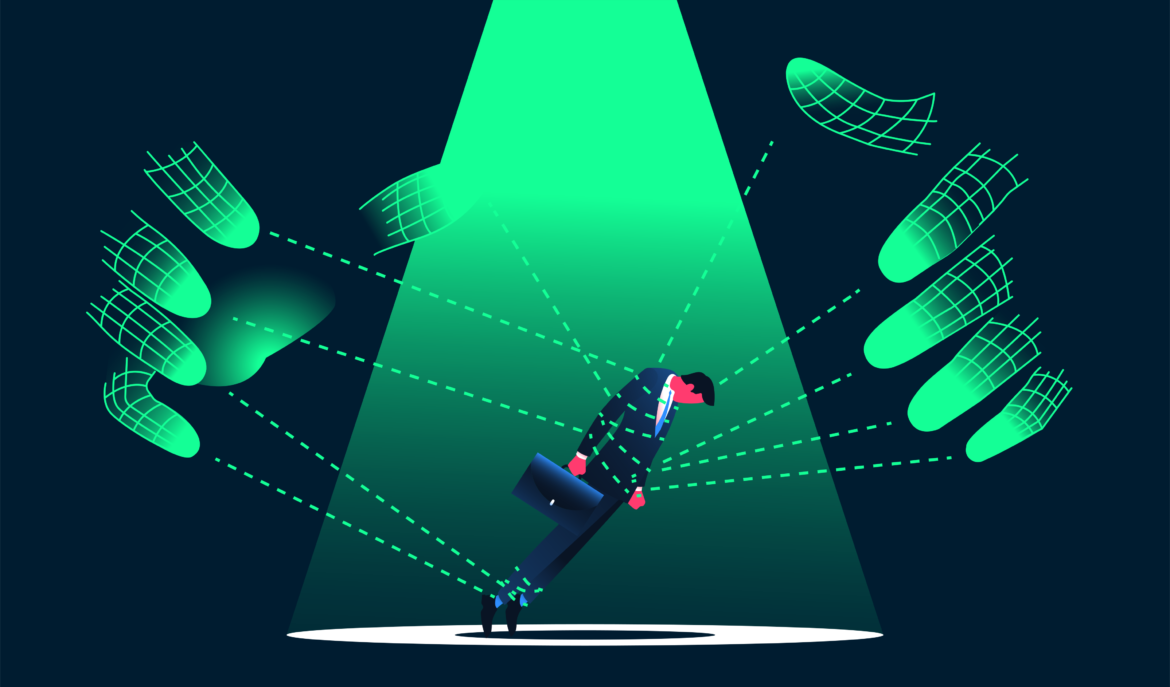

Artificial intelligence is increasingly woven into everyday life, from chatbots that offer companionship to algorithms that shape what we see online. But as generative AI (genAI) becomes more conversational, immersive and emotionally responsive, clinicians are beginning to ask a difficult question: can genAI exacerbate or even trigger psychosis in vulnerable people?

Large language models and chatbots are widely accessible, and often framed as supportive, empathic or even therapeutic. For most users, these systems are helpful or, at worst, benign.

But as of late, a number of media reports have described people experiencing psychotic symptoms in which ChatGPT features prominently.

For a small but significant group — people with psychotic disorders or those at high risk — their interactions with genAI may be far more complicated and dangerous, which raises urgent questions for clinicians.

How AI becomes part of delusional belief systems

“AI psychosis” is not a formal psychiatric diagnosis. Rather, it’s an emerging shorthand used by clinicians and researchers to describe psychotic symptoms that are shaped, intensified or structured around interactions with AI systems.

Psychosis involves a loss of contact with shared reality. Hallucinations, delusions and disorganized thinking are core features. The delusions of psychosis often draw on cultural material — religion, technology or political power structures — to make sense of internal experiences.

Historically, delusions have referenced several things, such as God, radio waves or government surveillance. Today, AI provides a new narrative scaffold.

Some patients report beliefs that genAI is sentient, communicating secret truths, controlling their thoughts or collaborating with them on a special mission. These themes are consistent with longstanding patterns in psychosis, but AI adds interactivity and reinforcement that previous technologies did not.

The risk of validation without reality checks

Psychosis is strongly associated with aberrant salience, which is the tendency to assign excessive meaning to neutral events. Conversational AI systems, by design, generate responsive, coherent and context-aware language. For someone experiencing emerging psychosis, this can feel uncannily validating.

Research on psychosis shows that confirmation and personalization can intensify delusional belief systems. GenAI is optimized to continue conversations, reflect user language and adapt to perceived intent.

While this is harmless for most users, it can unintentionally reinforce distorted interpretations in people with impaired reality testing — the process of telling the difference between internal thoughts and imagination and objective, external reality.

There is also evidence that social isolation and loneliness increase psychosis risk. GenAI companions may reduce loneliness in the short term, but they can also displace human relationships.

This is particularly the case for individuals already withdrawing from social contact. This dynamic has parallels with earlier concerns about excessive internet use and mental health, but the conversational depth of modern genAI is qualitatively different.

What research tells us, and what remains unclear

At present, there is no evidence that AI causes psychosis outright.

Psychotic disorders are multi-factorial, and can involve genetic vulnerability, neuro-developmental factors, trauma and substance use. However, there is some clinical concern that AI may act as a precipitating or maintaining factor in susceptible individuals.

Case reports and qualitative studies on digital media and psychosis show that technological themes often become embedded in delusions, particularly during first-episode psychosis.

Research on social media algorithms has already demonstrated how automated systems can amplify extreme beliefs through reinforcement loops. AI chat systems may pose similar risks if guardrails are insufficient.

It’s important to note that most AI developers do not design systems with severe mental illness in mind. Safety mechanisms tend to focus on self-harm or violence, not psychosis. This leaves a gap between mental health knowledge and AI deployment.

The ethical questions and clinical implications

From a mental health perspective, the challenge is not to demonize AI, but to recognize differential vulnerability.

Just as certain medications or substances are riskier for people with psychotic disorders, certain forms of AI interaction may require caution.

Clinicians are beginning to encounter AI-related content in delusions, but few clinical guidelines address how to assess or manage this. Should therapists ask about genAI use the same way they ask about substance use? Should AI systems detect and de-escalate psychotic ideation rather than engaging it?

There are also ethical questions for developers. If an AI system appears empathic and authoritative, does it carry a duty of care? And who is responsible when a system unintentionally reinforces a delusion?

Bridging AI design and mental health care

AI is not going away. The task now is to integrate mental health expertise into AI design, develop clinical literacy around AI-related experiences and ensure that vulnerable users are not unintentionally harmed.

This will require collaboration between clinicians, researchers, ethicists and technologists. It will also require resisting hype (both utopian and dystopian) in favour of evidence-based discussion.

As AI becomes more human-like, the question that follows is how can we protect those most vulnerable to its influence?

Psychosis has always adapted to the cultural tools of its time. AI is simply the newest mirror with which the mind tries to make sense of itself. Our responsibility as a society is to ensure that this mirror does not distort reality for those least able to correct it.

Alexandre Hudon, Medical psychiatrist, clinician-researcher and clinical assistant professor in the department of psychiatry and addictology, Université de Montréal

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.