By Rajiv Prabhakar, The Open University

European Equal Pay Day is the date when women – symbolically at least – start working for free because of the gender pay gap. This gap, of about a month and half of salary per year between men and women, means that from November 15 2024 women will effectively stop earning while their male counterparts continue to get paid.

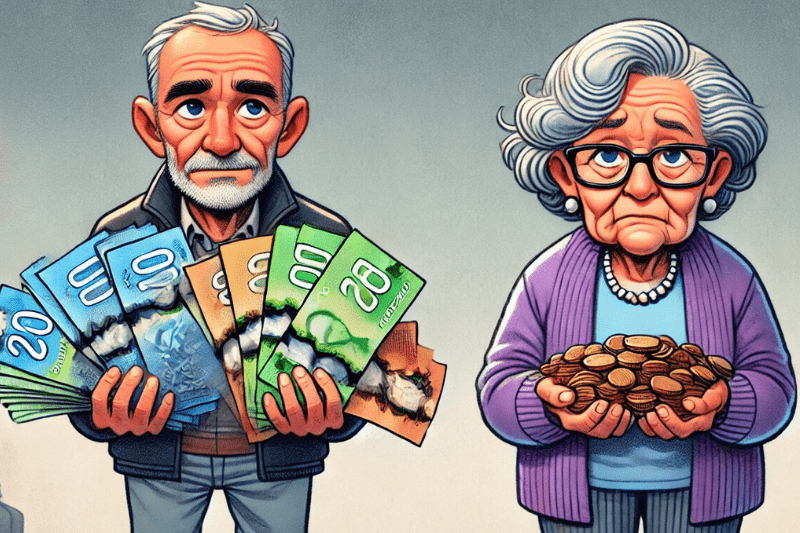

This gender pay gap is both well known and yet not fully understood. Women in general do a disproportionate share of unpaid caring and get lower pay. But what is much less known is how this gender pay gap is compounded once women leave the workforce and then go on to experience a gender pension gap. This can be around 35% in private pension wealth.

But to understand the cause of the pensions gap, we have to start with pay. The gender pay gap is usually based on the difference in average hourly pay between men and women. Official data uses the median person – that is the person in the middle of a spread of pay – to work out the average. But it is important to unpick differences between full-time, part-time and other types of work.

Looking at official figures for the UK, in 2024 average hourly pay for full-time workers was 7% less for women than men. But for part-time work, the average hourly pay for women was 3% higher for women than men. So it’s a complicated picture where men enjoy higher pay than women in full-time work but are paid less in part-time work.

However, part-time work is usually paid less per hour than full-time work and women make up a larger share of part-time workers. Looking at all workers, both full-time and part-time, the average hourly pay in 2024 was 13.1% less for women than for men. This is often the reported headline figure for the gender pay gap.

There is some good news though – the gender pay gap has been narrowing over the past 20 years. The gap for all employees more than halved from 27.5% in 1997 to 13.1% in 2024.

What causes the gender pay gap?

There is no single cause of the gender pay gap. One of the most important contributors is the greater share of unpaid caring that is done by women rather than men. Women are more likely than men to take time out of the workforce to raise children and more likely to work part-time while children are at school.

One way this is illustrated is how the gender pay gap changes with age. The 2021 census for England and Wales shows that the average age that women have their first child is nearly 31. In 2024, the gender pay gap for men and women aged from 22 to 29 for all employees is 3.4%. However, the gender pay gap begins to have an impact on women in their 30s and 40s, rising to 9.7% in their 30s and 16.5% in their 40s. So the pay gap widens during the years of raising children.

Much of this may be depressingly familiar. What is less reported however is how the gender pay gap continues to affect women beyond the workforce. Successive UK governments have taken steps to have greater equality between men and women in the state pension (although there is a debate about how these changes have affected women born during the 1950s).

In a knowledge exchange project I did at the House of Commons Library, I noted that the gender pay gap feeds directly into how much women save into private pensions. This occurs in two ways. If people spend time out of the workforce then they are less likely to add to a private pension. Second, being in lower paid or part-time work means that women then make lower contributions than men into private pensions.

The result is the gender pay gap is compounded into a much bigger problem of the gender pension gap.

Since 2017-18 all employers with 250 staff or more have been required to publish data on the gender pay gap. However, it was only in 2023 that the UK government published data for the first time on the gender pensions gap. This data suggested a gender pension gap of 35% in private pension wealth.

Tackling the roots of the gender pay gap then will improve not only the situation for women in the workforce but also will affect their outcomes in retirement. Women on average live longer than men. So women on average need more pension wealth to have the same amount of income per year during their retirement.

Regular reporting of the gender pay gap has helped, and reporting of the gender pension gap should highlight the wider impacts.

Paid childcare is likely to be vital for reducing the barriers that women face in entering the workforce. There are other potential policy changes to automatic enrolment into a workplace pension that could be helpful.

There is no quick and easy solution, and for millions of women who have retired already any change will come too late. But recognising that the gender pay gap has effects beyond the workforce is an important start.

Rajiv Prabhakar, Senior Lecturer in Personal Finance, The Open University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.