By Mary Jane Logan McCallum, University of Winnipeg

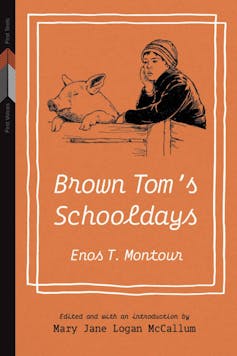

Brown Tom’s Schooldays, is a semi-autobiographical collection of stories about growing up in a residential school in Ontario in the early 1900s.

The author is the late Enos Montour, a Delaware writer from Six Nations of the Grand River. As the title suggests, it is an ironic play on Tom Brown’s Schooldays (1857), Thomas Hughes’s popular novel about his boyhood in an English school.

In Brown Tom’s Schooldays, instead of the main character being an English boy at an elite private boarding school, he is Tom Hemlock, a First Nations boy attending Mount Elgin Indian Residential School between 1910 and 1915. Montour’s narrative is the only known substantive writing by a Mount Elgin student. His stories unfold school life, illuminating the physical and social world of Mount Elgin in powerful ways.

A new edition of Brown Tom’s Schooldays has recently been published by the University of Manitoba Press Series called First Voices, First Texts. This series aims to reconnect contemporary readers with some of the most important Indigenous literature of the past, much of which has been unavailable for decades.

The series reveals the richness of these works by providing re-edited texts that give readers new insights into the cultural contexts of these unjustly neglected classics. The diversity and complexity of Indigenous writers and their work was not appreciated by publishers when authors like Montour attempted to have his book published in the 1970s and 80s.

As a historian and Canada Research Chair in Indigenous People, History and Archives at the University of Winnipeg, and band member of the Munsee Delaware Nation who has been engaged in community-based projects chronicling the history of Mount Elgin, I led the project.

In my introduction, I document Montour’s fascinating life and work and detail Brown Tom’s Schooldays’ publication history, drawing from documents from the United Church of Canada Archives, Trent and McGill University Archives, Library and Archives Canada, private correspondence and other sources. I also show how the book provides insight into the operations of Mount Elgin, as well as social and linguistic histories of the First Nations communities in the area.

20th century Indigenous print cultures

Montour, a minister with the United Church of Canada, published several of the early chapters of Brown Tom in United Church magazines.

After he retired, he gathered these and other Mount Elgin stories together and sought a church or trade publisher for the book. When no publishers moved, Montour felt frustrated that his work might be read as too “mild” for a reading public who expected sensationalized depictions of First Nations life.

In declining health, Montour ensured a legacy for the book by asking anthropologist Elizabeth Graham to transcribe, edit and photocopy the manuscript. Copies were made for family and friends. One copy of the manuscript was sent by Graham to the National Library in Ottawa. Until this fall, that was the only publicly accessible copy of the work.

For this new edition of Brown Tom’s Schooldays, with University of Manitoba Press editor Jill McConkey, I consulted with Graham, as well as Montour’s two granddaughters, Mary I. Anderson and Margaret McKenzie, about how we might frame the book. Using archival correspondence between herself and Montour, Graham wrote a new preface. Anderson and McKenzie shared family records, including photos, and wrote an afterword to the book.

This new edition of Montour’s book is a good reminder that formal published work accounts form a small fraction of the literature by and about Indigenous people and history. A much more representative field is produced in copy shops, and this self-published, limited-run “grey literature” is now held in archives across the country.

Industrial School from perspective of young boy

Brown Tom’s Schooldays is based solidly in a real place and draws from lived experiences. Like the central tension of Tom Brown’s Schooldays, Montour’s book is about moving toward adulthood and the meaning of that for First Nations students at the time. Montour’s layered story shows how, for “Brown Tom,” this journey involved learning and then working through self-doubt and prejudice and confronting the impossible choice of a white or Indian adulthood.

Montour’s formal education at Mount Elgin was based on set curriculum that endorsed colonial domination, racism and discrimination against people of colour and Indigenous people. Moreover, a federal Indian Residential School, Mount Elgin’s purpose was to facilitate assimilation of First Nations children, and this happened in an underfunded, carceral and abusive setting. Mount Elgin, like other residential schools, emphasized children’s manual labour more than academics.

In spite of this early education, Montour loved reading and writing, and he brought this love to his stories of Mount Elgin and the surrounding area, giving the school character and beauty and students humour and agency. The stories are at times strikingly sentimental.

When I first read this collection, I did not know what to think of it. For me, Montour’s consistent references to the Bible and classic works of English literature did not fit with what I expected in an Indian Residential School memoir. I chaffed when reading Montour’s characters written in terms that seem to accept standard racist stereotypes of First Nations at the time. His representation of the early 20th century seemed too funny, or rosy, too Anglophile and too naive.

At the same time, I knew that Montour wrote stories true to his experience, as he understood it, and by his ironic play on English literature through the eyes of a First Nations boy. This way of writing is a window into a sense of humour and way of telling what mattered that reminded me of people of my great-grandfather’s generation.

There is backlash to Indian Residential School historical research and a hardcore fringe who deny that the research of the National Truth and Reconciliation Commission and trained professional historians is reliable. They deny systemic harms of the Indian Residential School system primarily by likening it to a slightly harsher version of boarding schools.

But I don’t think Montour would have feared how the book would be received and read. He writes compellingly about youth, school life and friendship, but also about the callous and disorienting experience of arriving at Mount Elgin and the everyday pervasive hunger and homesickness felt there.

He also describes extraordinary moments, including the death of a fellow student, Noah, who had tuberculosis. Short, moving and profoundly troublesome, this chapter shows the pervasive apathy towards student life at Mount Elgin and the ungreivablity of student death.

Ultimately, even in retirement and ill health, Montour insisted on completing the book and making it accessible because the stories mattered to him. And they matter to us, too.

Brown Tom’s Schooldays can be purchased from anywhere you buy books.

Mary Jane Logan McCallum, Professor of History, University of Winnipeg

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.