By Christopher A. Cooper, L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa

When thinking about what affects good governance, most citizens, pundits and even political scientists tend to focus on the fast-paced world of electoral politics.

But for all the talk of politicians, parties and Parliament, there in the shadows lies the most indispensable but poorly understood political institution in Canada: the public service.

But not all is well at the moment with Canada’s federal public service. In a forthcoming study to be published in the Review of Public Personnel Administration, my co-researcher and I find that the inability of both French and English-speaking federal public servants to work in their official language of choice is pushing them to consider quitting their jobs.

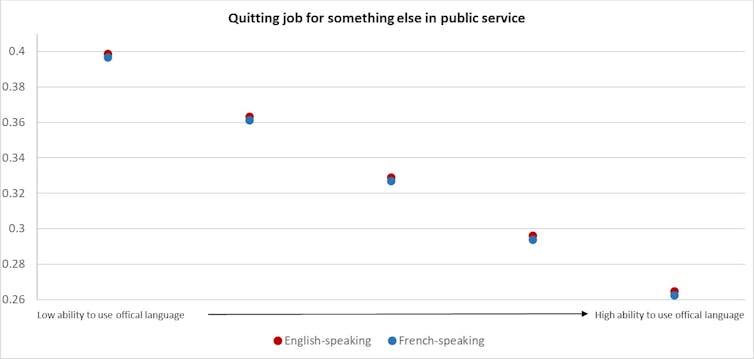

Approximately 40 per cent of English and French-speaking public servants, citing a low ability to use their official language at work, said they intended to quit their jobs for something else within the public service, whereas the probability of quitting was only 26 per cent among public servants expressing a high ability to use their official language at work.

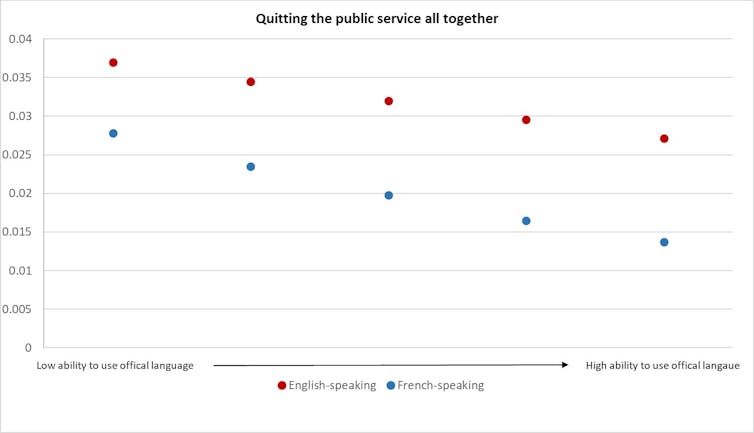

More drastically, when asked about quitting the public service completely, we find a similar — although less pronounced — relationship. Four per cent and three per cent of English and French-speaking public servants, respectively, who reported a low ability to use their official language of choice said they intended to quit, whereas the probability of doing so was only three per cent (English) and one per cent (French) among public servants reporting a high ability to use their official language at work.

These findings aren’t just worrisome for a public service seeking to retain talent. It should be deeply troubling for us all given the essential role the permanent public service plays in promoting good governance in Canada.

The role of the public servant

Public servants play a vital role in governing. Working alongside politicians, stakeholders and citizens, public servants identify public problems, design policy solutions and implement programs.

But more than this, public servants play an essential role in promoting good governance. They hold a great deal of knowledge and experience. Drawing upon their expertise, public servants also provide politicians with frank and fearless advice.

These qualities did not emerge by chance. Rather, they were sought after by Canadian reformers late in the 19th and early 20th century who were unhappy with the low level of expertise and high level of turnover within the bureaucracy following every change in government, which defined an earlier era of rampant patronage.

Reforms such as the 1854 Northcote-Trevelyan Report in the United Kingdom, tabled when Canada was still a British colony, and the Civil Service Act of 1918 improved the public service by ensuring that public servants would be hired according to merit and given permanent jobs.

This protected public servants’ careers against the type of post-election changes experienced by the politicians and parties who make up Parliament and is common to any healthy democracy.

Now, more than 100 years after these reforms, organizations like the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) still promote a permanent public service as a key component of good governance.

Bilingualism in Canada’s public service

But while the careers of Canada’s federal public servants remain protected from political influence, not all is well when it comes to permanence.

A present threat stems not from electoral politics, but from a work environment issue pertaining to the public service itself: the inability of some public servants to work in their official language of choice.

Although the early 20th-century reforms established permanent public service careers, there was a growing desire to make Canada’s bureaucracy better reflect its linguistic diversity by the 1960s.

Despite being a bilingual country, the public service was predominately staffed by English-speaking Canadians. In the 1940s, only 12 per cent of federal public servants were French-Canadian even though approximately one in three Canadians were French-speaking.

In 1969, the Official Languages Act made French and English the official languages of the public service. The Official Languages Act of 1988 further affirmed this, and specified that federal public servants had the right to work in the official language of their choice in bilingual regions of Canada.

‘Psychological contract’

The ability of some federal public servants to work in the official language of their choice can be understood as a “psychological contract” — an agreement between an employee and their employer concerning their work environment.

Research has found that an employer’s failure to respect the terms of a psychological contract leads employees to become frustrated and dissatisfied with their jobs, and sometimes, as was the case with the problematic Phoenix pay system, this frustration can even push employees to quit.

While English and French enjoy equal official status in Canada’s bilingual public service, in reality — and for a variety of reasons — this is not the case.

The more cynical in Ottawa will tell you that the two official languages in Canada’s government are “English and Translation.” A recent survey by the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages found that 44 per cent of French-speaking public servants in bilingual regions were uneasy with using (or asking to use) French at work, compared to 15 per cent of English-speaking public servants with regards to English.

But are difficulties to work in one’s official language of choice an unfortunate, but accepted, reality for Canadian public servants?

Or does it have more serious negative consequences on the attitudes and behaviour of public servants, including their intention to quit their jobs, than is typical for employees experiencing a psychological contract breach in the conditions of their work environment?

Quality of governance

My co-researcher and I used data from the Public Service Employee Survey and found this inability to use their official language of choice at work is pushing some to make the aforementioned considerations: to either leave their jobs for something else within the public service or to quit entirely.

While we might expect this relationship to be more pronounced among French-speaking public servants, we found it’s leading both English and French-speaking public servants to consider quitting.

Given the critical role the permanent public service plays in governance, our findings are worrisome, and raise concerns not only about the public service’s performance, but about the overall quality of governance in Canada.

Christopher A. Cooper, Associate Professor of Public Management, L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.