By Leonora Risse, University of Canberra

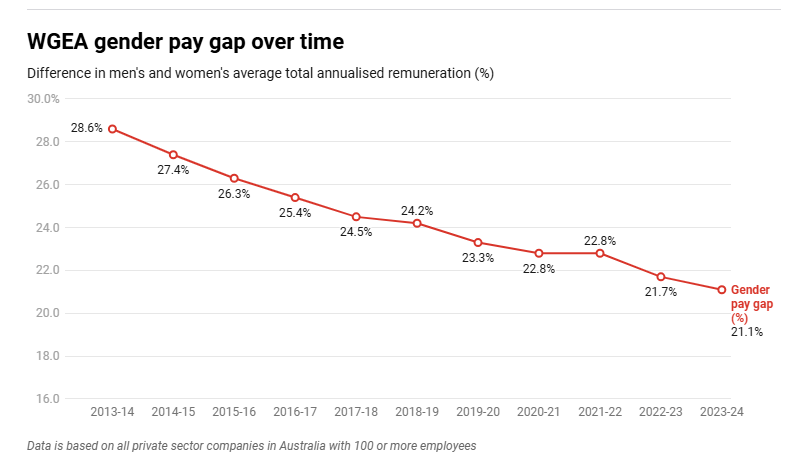

Australia’s gender pay gap has been shrinking year by year, but is still over 20% among Australia’s private companies, a new national report card shows.

But that gender gap is even bigger at 25% among chief executive officers, according to figures collected for the first time in 2023–24.

And the widest gap of all is among older workers, with women in their late 50s typically earning $53,000 less each year than men the same age.

The release of the scorecard coincides with the federal government announcing it will introduce legislation this week requiring employers to set gender targets for boards, for narrowing the pay gap and for providing flexible work hours.

These and other measures will apply to companies with 500 or more employees. They build on legislative changes that enables the Workplace Gender Equality Agency to publish the size of their gender pay gaps, which came into effect this year.

Tracking Australia’s gender pay gap

Each year, the gender equality agency measures the gender equality performance of all private sector employers with 100 or more employees. This adds up to more than 7,000 employers and 5 million employees nationally.

Drawing on data collected in the annual employer census, the agency looks at several key indicators including gender composition of the workforce, gender balance of boards and governing bodies and equal pay for equal work.

One important indicator is the gender gap in average total remuneration. This is calculated for all employees – full-time, part-time and casual – by converting employees’ pay into a full-time annualised equivalent.

The gap continued to shrink in the past year to 21.1%. This has been largely fuelled by growth in the pay of the lowest-earning women in the workforce.

This came about, in part, because in June 2023, the Fair Work Commission awarded a 15% minimum pay rise to several aged care awards, where women hold 80% of jobs. Raises were also given to the retail trade, accommodation and food services sectors, also large employers of women.

Another reason the gap narrowed was because the remuneration of women managers rose by 5.9% from 2022-2023, compared to men’s which increased by 4.4% over the same period.

A bigger gap among high earners

The increase was particularly significant for high earning women (up 6.3%) compared to high earning men (4.1%). However, men still outnumber women in management, holding 58% of positions.

For the first time in 2023-24, the agency collected CEO salaries. The gender gap in CEO total remuneration was 25%.

Just one in four CEOs are women, and the gender pay gap for these key roles is the largest of all management roles. Women CEOs are paid, on average, $158,632 less total remuneration than men.

When CEO salaries are added into the mix, the overall gender pay gap stretches to 21.8%.

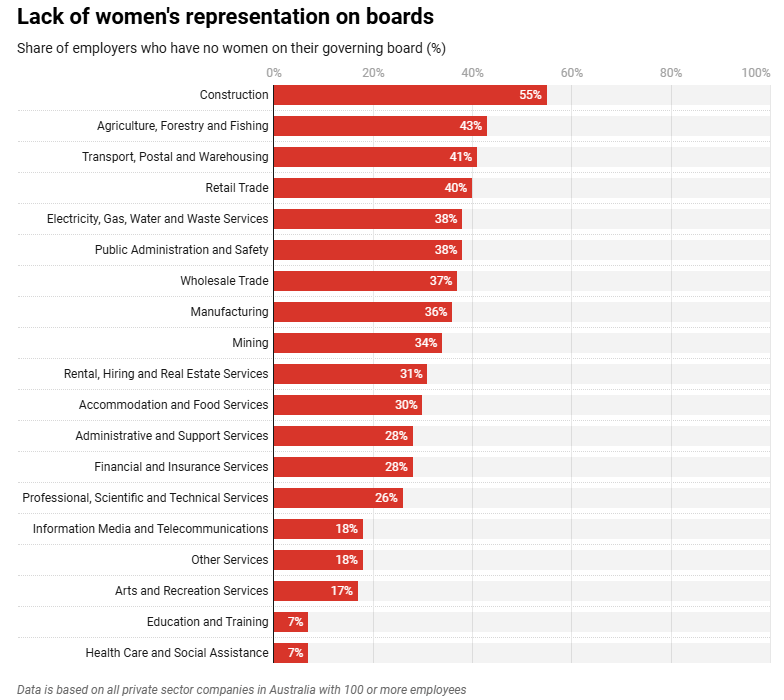

Little change for women on boards

The gender agency knows that women’s representation on governing boards matters for steering organisational change towards gender equality, monitoring these changes on the scorecard.

However the overall percentage of women on boards has hardly budged in recent years, at around one-third.

And about one-quarter of companies have no women on their governing board at all. This share is even higher in male-dominated industries, such as construction where the boards of 55% of companies are all men.

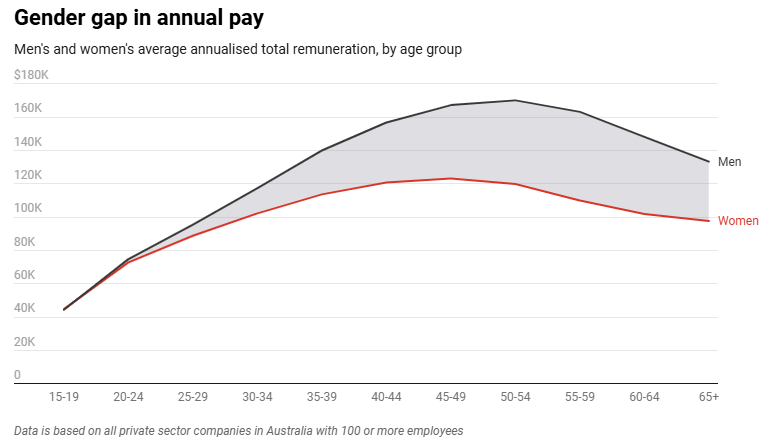

Women in their late 50s face the biggest pay gap

In dollars, it means Australian women are earning, on average, $28,425 less each year than their male colleagues.

This gap widens further among older workers. At its widest point, women aged 55 to 59 years are earning $53,000 less each year than men – a gap of 32.6%.

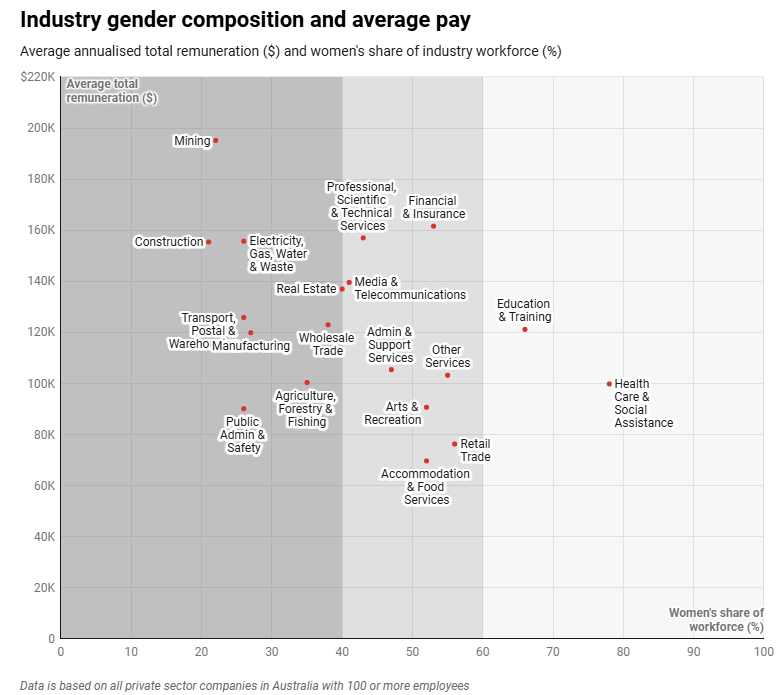

One of the big drivers of this pay gap are gender patterns in different industries and occupations

The gender agency’s scorecard shows that half of all private sector employees work in an industry that is either male-dominated or female-dominated, meaning its workforce least 60% of a single gender.

It’s been a longstanding feature of the workforce that male-dominated industries outstrip the average earnings are female-dominated industries of education and training, and health care and social assistance.

How supportive are employers

The workplace gender agency also measures employers’ policies supporting work and family balance, such as flexible hours and extra paid parental leave on top of minimal government provisions.

The finding that more employers are offering paid parental leave, rising from 63% to 68% in the past year, is a tick on the scorecard.

Men’s involvement in caregiving has a direct impact, enabling women’s involvement in the workforce. The proportion of parental leave being taken by men is up from 14% to 17%.

These improvements are set to increase under the government’s new legislation.

Providing a safe workplace

The final indicator on the scorecard looks at employers’ actions to prevent and respond to sexual harassment and discrimination in their workplace, as required under new Respect@Work laws.

Almost all (99%) of employers report having a policy in place. But there is scope for improvement in other ways.

Almost half (40%) don’t monitor the outcomes of sexual harassment and discrimination complaints and half don’t review the policy and consult with employees. As well, about 25% don’t incorporate inclusive and respectful behaviour into regular performance evaluation.

How reporting can drive change

As with any report card, there are marks for effort.

In the last year, 75% of companies reported they had analysed their own organisation’s gender pay gap and had made changes. This was up from 60% the previous year.

The gender agency attributes this to the publication of individual organisation’s gender pay gaps for the first time earlier this year.

Almost half (45%) of employers are now setting goals to improve gender equality. This includes targets to boost the number of women in management, reduce the gender pay gap and to achieve a gender-balance in their governing body.

These higher aspirations are likely to also be a response to plans to make target-setting part of the requirements for bidding for government contracts.

These changes show how incentives can bring about improvements. They arose from the 2021 Review to the Workplace Gender Equality Act that used research-based insights, data and community consultation to develop practical steps to reduce the gap and improve conditions for women.

Leonora Risse, Associate Professor in Economics, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.